Alex Craighead is an Australian born New Zealander who trained as a chef, before moving to Western Australia for the warm weather, and to study accounting.

“I moved to WA because I was so sick of the cold in Wellington,” says Alex. “I didn’t have very much money and the only place we could go to get a cheap drink was to do a wine tasting. So, we’d visit Swan Valley often and one day I sat down with one of the winemakers there, and as we were talking I thought all of this is actually quite interesting.”

“People almost get myopic in their approach to winemaking because they’ve only ever seen it done one particular way”

Alex returned to New Zealand and started studying viticulture and oenology at Lincoln University.

“After I graduated I did a horrendous amount of vintages around the world to gain as much experience as I could,” says Alex.

Clocking up numerous vintages in the Hunter Valley, Yarra Valley, Mornington Peninsula, McLaren Vale, Riverland, Central Otago, Marlborough, Waipara, Hawke’s Bay, Wairarapa, Coscisa, Bordeaux, Burgundy, Pied de Monte, Washington State, Okanagan, and many more places, taught Alex that winemakers, even from the New World, can easily become set in their ways.

“People almost get myopic in their approach to winemaking because they’ve only ever seen it done one particular way,” says Alex. “There’s so much to winemaking that can be quite prescriptive, and you kind of expect that in the Old World wine regions. But here, in New Zealand and in Australia, we can be just as rigid, and it upsets me because we started off with such a hiss and a roar of wanting to be different.”

(Enter, stage left, natural wine)

Natural wines have been embraced in Australia by young winemakers searching for something new, inspired, mostly, by their experiences making wine abroad, particularly in France, where modern incarnations of natural wine were said to have begun in Beaujolais, France, in 1978. Guys like Tom Shobbrook, Anton Von Klopper, and James Erskine, are pretty much the (unofficial) founding fathers of natural wine, in Australia. Recently, they’ve been the inspiration to many budding young winemakers to try something different and search for something new, in wine.

“Nothing’s remedial when you’re making natural wines,” says Alex. “You have to own your problems and wear them on your sleeve. You can’t forget about something and just fix it later on, if the wine has a problem because you weren’t being careful enough, it’s fucked and you just have to accept it. Unless, you’re happy about pouring 300L down the drain, you have to be ultra careful when making wine naturally.”

“Most winemakers don’t ask enough questions like, ‘why are we doing it like this?'”

This recent explosion of the natural wine ‘scene’ in Australia, hasn’t quite made it across the ditch to New Zealand, just yet. They’ve been far too busy concentrating all their efforts on inventing Pavlova, instilling a successful sustainable winegrowing program, integrating with their indigenous peoples, considering, and sensibly debating, changes to their national flag, setting targets to have 20% of the country’s vineyards certified organic by the year 2020, and winning the Bledisloe Cup.

But, the times are indeed ‘a-changing’.

“Most winemakers don’t ask enough questions like, ‘why are we doing it like this?’,” says Alex. “Because usually the answer is, ‘well, that’s just the way I was taught’, but that’s not really good enough. Everyone should want to experiment with their technique, as much as possible.”

Alex’s wine label, Don, is made from fruit grown in the Wairarapa wine region of Martinborough from vineyards that, he says, are in conversion to organics. Martinborough is a small town, 65km south west of Wellington, that was founded by New Zealand politician, John Martin, who humbly named the town after himself. He designed the streets to resemble the Union Jack, and even named some of them after foreign cities he had visited.

Most of the vineyards in the Wairarapa have been planted on flat agricultural land, because, in a past (less glamorous) life, many of the grape and wine growers used to be sheep and cattle farmers. In step with his ideas for more progressive winemaking in New Zealand, Alex has his sights set on the hills and slopes that skirt around Martinborough.

“I don’t think some of this region’s best vineyards have even been planted yet,” says Alex. “A lot of the vineyards in New Zealand seem to have only been planted because of convenience. Martinborough is only planted on the flats because it is easy to farm, and it’s why the vine rows are usually 2.7m wide… because they had tractors that couldn’t go down anything that was smaller.

“There’s so many great spots up amongst the hills of Wairarapa,” continues Alex, “with so much potential for great wines to be grown there.”

But, planting a new vineyard these days is expensive, so for now, Alex works with what he’s got, determined to inject a more progressive approach into his own wines.

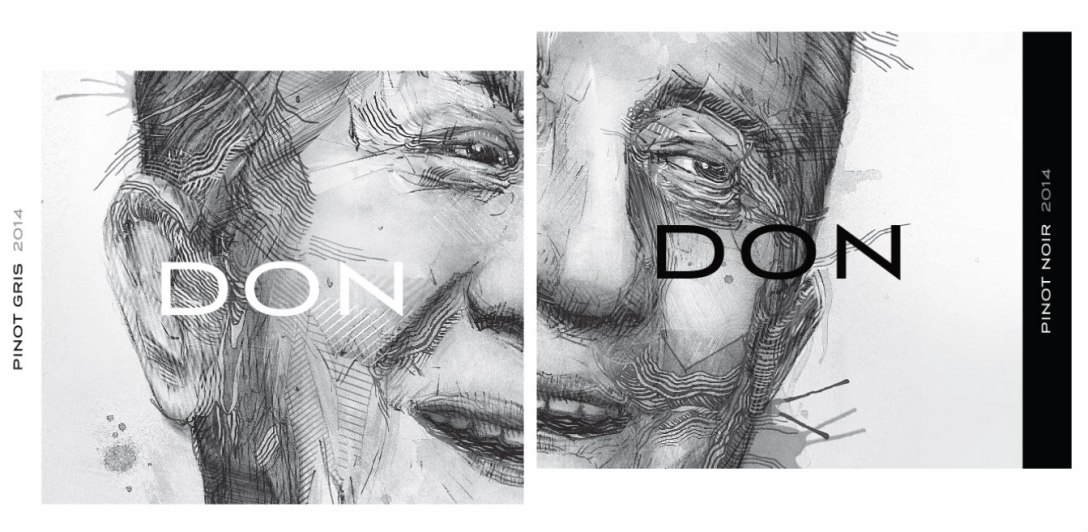

“Don is named after my partner’s grandfather, Don Ramon,” explains Alex. “He’s 96 years old and lives in Argentina. He’s been a farmer all his life and just a very simple, honest man, which is how I want my wines to be.”

Don consists of two wines, pinot gris and pinot noir, made from fruit grown in Martinborough. The wines are fermented using wild yeasts (from a starter in the vineyard), and made without any additions, minimal to no oak influence, no fining or filtration, and, “a tiny tickle of sulphur just before bottling.”

The Don pinot gris is left on skins for nearly 40 days after the ferment has finished, because Alex believes the skin of the pinot gris berry is where all of the flavour lies.

“All the flavour is in the skin of pinot gris, which is why I want to do a skin ferment,” explains Alex. “I think a lot of pinot gris is anaemic looking, and tasteless, whenever it’s made into a white wine. Most are lacklustre and have no style or identity. They’re either sweet or dry.”

“I’m not a big fan of wines that take themselves too seriously”

Alex’s Don pinot noir is fermented using between 40% and 60% whole bunch. Whole bunch, or whole cluster, is when the entire grape bunch – grapes, stems, seed, and all – is put into the ferment together to try to add an extra level of complexity to the finished wine.

“I’m really big on whole cluster for pinot (noir)” says Alex. “It adds an elegance to the wine, and I really like the carbonic effect you get by fermenting whole berries in tact. It adds to the herbaceousness that Martinborough reds seem to have.”

–

Alex wants to push the progression of winemaking in New Zealand, by experimenting more and more with the techniques he learnt at university, and then doing vintages around the world, but not ever for the sake of drinkability and flavour.

“I make wines that I, myself, would want to drink,” explains Alex. “I’m not a big fan of wines that take themselves too seriously, or wines that need to be aged for a million years before they can be drunk. I want to make fun wine that people will drink and enjoy.”

–

D// – The Wine Idealist

–

Links and Further Reading

- Don Wines

- Martinborough (Wikipedia)

- Martinborough (map)

- Click to Support The Wine Idealist!